Cracks in the ice: why the race to the North Pole isn't over

As Denmark becomes the latest country to formally claim ownership of the North Pole, Daniel Fahey recounts the bizarre tale of Arctic exploration so far.

A few weeks before Christmas, just as children were sending notes to Santa Claus, the Danish government penned a letter to the United Nations asking for a very special present: ownership of the North Pole.

It was the latest twist in the tale of Arctic ownership, which has iced friendships, melted reputations and caused cracks to appear across North America, Russia and Scandinavia.

Denmark’s request, justified on account of its claim over Greenland, countered similar claims from Russia, which, in an act of geopolitical muscle-flexing, nailed its colours to the North Pole seabed in 2007.

“The aim of this expedition,” Russia’s Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, declared at the time, “is not to stake Russia's claim but to show that our [continental] shelf reaches to the North Pole.”

It sounded like a claim to Canada, though, which has long had eyes for the North Pole.

“This isn't the 15th century,” lamented Canadian Foreign Minister, Peter MacKay. “You can't go around the world and just plant flags and say: ‘We're claiming this territory’.”

With climate change set to open up the resource-rich Arctic, competition for the North Pole will continue to heat up.

The story's undercurrent of greed, rivalry and dirty tricks already draws parallels with one of the greatest battles of modern travel: the race to the North Pole.

Poles Apart

The Cook Expedition stand at the North Pole

The Cook Expedition stand at the North PoleCreative Commons / Cook Expedition

It was noon on 21 April 1908 and the dark purple shadow of American Dr Frederick Cook trailed nearly 9m (30ft) behind him. Ahwelah and Etukishook, the two Inuit companions who had travelled with Cook from Annoatok in Greenland, stood beside him in thick furs.

The broad-bearded explorer took out his custom-made sextant to measure their exact location. Taking the reading, his heart began beating frantically – the instrument showed that they were the first to stand (as near as Cook believed was possible) at the North Pole.

Scribbling alongside several geographical observations in his grubby, pemmican-greased diary, Cook noted: “Nothing wonderful; no Pole; a sea of unknown depth; ice more active; new cracks; open leads; but surface like farther south. Overjoyed but find no words to express pleasure. So tired and weary! How we need a rest!”

By the time a ghost-written account of his journey came out, Cook's words were more poetic. “I felt the glory which the prophet feels in his vision, with which the poet thrills in his dream,” gushed his book, My Attainment of the Pole.

After taking notes, Dr Cook unrolled a large American flag and attached it to a pole planted atop the igloo that Ahwelah and Etukishook had built nearby. It flapped in a light, southerly wind as all three posed for a photograph.

Almost exactly a year later, Cook still hadn't returned from the Arctic and was presumed dead.

By this point, a second American explorer, Rear Admiral Robert Peary, was making his way to the North Pole.

Having failed in a previous attempt to reach the Pole, the saggy-eyed explorer was once again overcome by the gravity of the challenge.

“With the Pole actually in sight I was too weary to take the last few steps,” Peary wrote in The North Pole: Its Discovery in 1909 under the auspices of the Peary Arctic Club.

“The accumulated weariness of all those days and nights of forced marches and insufficient sleep, constant peril and anxiety, seemed to roll across me all at once,” he added. “I was actually too exhausted to realize at the moment that my life's purpose had been achieved.”

Peary and his team planted five flags at the North Pole, including an American standard made of silk, which Peary’s wife had given him 15 years earlier.

Then they turned for home, believing they were the first to break hallowed ground.

By the end of the decade, however, both North Pole expeditions were embroiled in scandal: neither was thought to have made it.

Lies, bribes and enquiries boiled over into an ugly media scrap worthy of a Madison Square Gardens boxing bout: it was Cook vs Peary, trash-taking, toe to toe.

Cold Waters

Captain Bernier claiming Arctic territory for Canada in 1909

Captain Bernier claiming Arctic territory for Canada in 1909Creative Commons / Wikimedia Commons

If events were about to turn nasty in New York, the gloves became lead-weighted in Canada as a German-built barquentine, the Arctic, traversed the Arctic Archipelago under the eye of Captain Joseph-Elzéar Bernier.

Rotund, with a ship-rope moustache, Bernier was a patriotic Canadian with seafaring in his blood; a man with eyes on becoming the first person to officially stand at the North Pole.

The Canadian government, however, had other ideas. They wanted the Arctic to patrol the waters around Hudson Bay, managing whalers and foreign sea merchants.

The Arctic launched in 1904 and Bernier towed the line, kind of. As requested, he patrolled the waters, but during his voyages he started claiming islands across the Arctic Archipelago for Canada – without governmental authorisation.

If he came across a native Inuit, he would often invite them to the ceremonies surrounding the taking of the islands. He’d serve food upon the Arctic and encourage elders to mark where they’d travelled upon maps. All would share cigarettes and sweet tea.

Then, at Melville Island on 1 July 1909, Bernier took the lot.

Using a law from the late Middle Ages known as the sector principle, Bernier claimed all territory between Canada’s eastern and western borders up the way to the North Pole. A plaque went up; camera shutters came down.

It was a short-lived triumph.

The claims were rejected by the Canadian government. They disliked Bernier’s audacity, and his assumed authority, in claiming the lands.

When they finally acknowledged their possession in 1925, Russia (then the USSR) was triggered into a response: their Arctic Decree of 1926 declared that all lands and islands between the USSR and North Pole belonged to them. It was colonial checkmate.

If Canada wanted to own the North Pole, they’d have to think outside of the box, and by the time the Cold War arrived, they’d initiated a highly controversial plan.

Given The Cold Shoulder

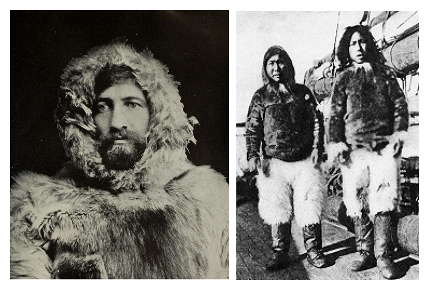

Cook in his Arctic furs and Ahwelah and Etukishook

Cook in his Arctic furs and Ahwelah and EtukishookCreative Commons / Brown Bros / Cook Expedition

By then, Dr Frederick Cook would be dead; his reputation in tatters.

For Cook, the return from the North Pole was gruelling: they missed cached food supplies, were pushed off-course by ice drifts and laboured over partly-frozen straits, which could only be passed using a canvas canoe. Progress was glacial.

Some 483km (300 miles) from Annoatok, their furs began to split. Food rations all but ran out, and they survived on duck caught using sling shots.

When they finally lumbered into Annoatok in April 1909, they were gaunt. They’d even lost the strength to haul their broken sledge the final 32km (20 miles). Inuit were sent to retrieve it.

It took days for Cook to regain his weight and strength, but while he did, he befriended a fellow American, Harry Whitney, who was in Greenland to hunt Arctic hare, bear, walrus and musk ox.

Whitney, a wiry huntsman from New Haven in Connecticut, had travelled north in July 1908 upon S.S. Roosevelt, the ship that carried Robert Peary and his expedition team to the Arctic Circle.

“I have reached the pole,” Cook conceded to Whitney, urging him to keep the news secret until he could announce it to the world himself.

Cook then set off for Upernavik, Greenland, hoping to catch a mail boat to Umanak, also in Greenland, where government steamers headed onto Europe. From there he could break his news before heading back to the US.

He believed this convoluted route would have him home by July.

Knowing that he’d have to cross glaciers and mountains to get to Upernavik, he took up Whitney’s offer to look after any non-essentials for the journey.

He left instruments, notes and papers with Whitney, even his American flag. His friend promised to transport them back to New York on the next available ship.

Shipping schedules meant Cook didn't leave Greenland until August. When he finally managed to secure a passage to Copenhagen, aboard the Hans Egede, Cook recounted tales of his trip to scientists and journalists.

Suitably impressed, the ship’s captain suggested an unscheduled stop at Lerwick, the main port in the Shetland Islands, so Cook could telegraph the New York Herald with news of his achievement.

When it hit the newsstands, it was the scoop of the year.

But by the time Peary caught wind of it from Inuit in Greenland, he started to play dirty.

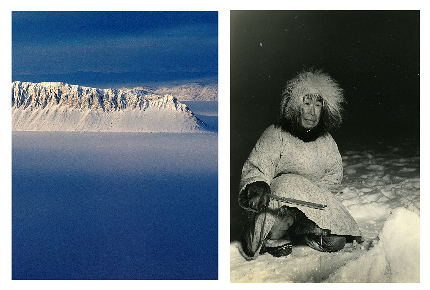

The Horrors Of High Arctic Relocation

Ellesmere Island in summer and an Inuit ice fishing

Ellesmere Island in summer and an Inuit ice fishingCreative Commons / NASA ICE / born1945

Peary’s underhandedness would prove nothing compared to that of the Canadians in the 1950s.

As the Cold War froze relations between East and West, the Arctic became strategically important.

Not only did it provide the shortest route for long-range bombers and submarines to take aim between the USA and Russia, but it was seen as an important defensive point for the West.

Around this time, Americans started outnumbering ‘white’ Canadians on some islands. They had opened weather stations and airfields across the more remote land masses, and the government feared that nations were disregarding Canadian ownership in the Arctic.

In an attempt to reclaim sovereignty, they committed what would go on to be described as “one of the worst human rights violations in the history of Canada”.

The government opened Royal Canadian Mounted Police outposts across the islands to reassert control, but soon decided that they needed Canadians to be living there too.

Simultaneously, the overhunting of caribou and a fall in the price of Arctic fox fur had left a growing number of Inuit in northern Quebec struggling for survival.

Facing an increased Inuit welfare bill, the government felt they could solve both issues in one swoop: by relocating Inuit families to the farthest islands.

Families from Port Harrison, where the majority of the welfare was handed out, were the first to be asked.

Officials were told to explain the harsh conditions they’d encounter, including the long, sunless winters and the single supply ship trips that would only arrive once a year.

They also gave them the choice to return home after a year.

Several families were sent to Ellesmere Island, a massive land mass that puffs out of northeast Canada like the smoke of a chimney. It shows the earth in all its rough, naked glory: there are no scars of car highways, no houses of decoration; it’s so remote it stunts trees; the silence deafens as much as the snow blinds.

When the Inuit arrived in 1953, it soon became apparent how underprepared they were. In The Long Exile, author Melanie McGarth wrote that the government shipments for the families lacked rifles, snow knives, fish hooks and first-aid supplies. The fingerless mittens they’d been sent wouldn’t stop frostbite; the overalls were oversized.

The 300 caribou skins they’d been promised turned out to be 12 heavy buffalo pelts.

The government had also declared Ellesmere Island a nature preserve, so the Inuit were limited in the number of caribou or musk ox they could kill for food or for fur.

Survival was nearly impossible: the Inuit knew nothing of animal migratory routes, the lungs of their dogs bled in the dry winds, and the bleak, black winter made any journey, no matter how short, torturous.

McGarth notes that in a battle to stay alive, Inuit ate ptarmigan feathers and boiled hare skin boot liners for broths. They chewed on seagull bones. Sick dogs were eaten, as were any puppies that died. The dogs, meanwhile, were fed on the diarrhoea and vomit of children, rather than letting it go to waste.

The promises to return home after a year were never honoured and the North Pole still wasn’t Canada’s.

The Race To New York

A celebratory banquet for Frederick Cook at Waldorf Astoria

A celebratory banquet for Frederick Cook at Waldorf AstoriaCreative Commons / Geo. R. Lawrence Co.

Rewind to 1909 and the race to the North Pole had become the race to New York.

Desperate to know if Cook had beaten him to it, Peary started interrogating people in Annoatok. Whitney divulged little, except to confirm that Cook was alive, while Ahwelah and Etukishook (who were quizzed upon the Roosevelt) failed to understand Peary’s questioning – he hadn’t mastered the native tongue.

As the S.S Roosevelt prepared to set sail for New York, Peary offered Whitney a lift home, but there was a catch: he couldn't bring Cook’s belongings with him. Reluctantly, Whitney left his friend's instruments and records behind. They haven't been seen since.

By the start of September 1909, the ship had reached Indian Harbour, Labrador on its way to New York.

“Stars and Stripes nailed to North Pole”, Peary flashed over to the New York Times from a wireless station.

Two days later, the Roosevelt docked again. “Don't let Cook story worry you. Have him nailed,” Peary added to his first dispatch.

Incredibly, both arrived back on shore on the same day. Cook received a hero’s welcome in New York Harbour: a wreath of white roses was hung from his neck as he paraded in front of the press. Well-wishers waited outside his Brooklyn home.

Peary, meanwhile, stepped ashore in Nova Scotia and headed south to meet two officers of the Peary Arctic Club: Herbert Bridgman and its President, Thomas Hubbard.

By the time the train rolled into Maine, Hubbard was ready to start the defence of Peary’s expedition, a trip he’d helped fund. He told the papers that Cook should submit his records to the authorities, adding: “What proof Commander Peary has that Dr Cook was not at the pole may be submitted later.”

The Peary camp started to discredit Cook’s character.

Stories started appearing in the press questioning Cook’s achievements.

The Peary Arctic Club released a signed statement by Cook’s Alaskan climbing guide, Edward Barrill, that said they had not been the first to conquer Mount McKinley in 1906 – they hadn’t even reached the summit. The New York Herald later reported that Barrill was paid handsomely to say so.

Soon, a transcript of Ahwelah and Etukishook’s questioning upon the S.S. Roosevelt was released by Peary. It said that Cook had only travelled a few days north on the ice cap.

Word then reached Cook about Whitney leaving his instruments and records in Greenland. Seized with heartsickness, Cook felt crippled.

To make matters worse, the University of Copenhagen wouldn’t authenticate Cook’s achievements without the original documents. He was trapped.

Peary’s claim, meanwhile, was officially verified by the National Geographic Society, who had part-funded his trip.

Still, just as there would be in the race to own the North Pole, there was one more surprise to come.

The Arctic Heats Up Again

A US ship breaks through the Arctic ice on a geological survey

A US ship breaks through the Arctic ice on a geological surveyCreative Commons / U.S. Geological Survey

“THERE MAY BE BLOOD” screamed a headline in Popular Science during the summer of 2008.

It was the story that Arctic countries had been waiting for: geologists announcing that there may be 90 billion barrels of oil and 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the Arctic Ocean.

Governmental ears pricked again.

Norway, Russia and Canada, who had already ratified the United Nations in an attempt to own part of the Arctic Ocean, sat back and waited for others to show their cards.

Denmark did just before Christmas, but still no-one owns the North Pole.

Nor did Peary.

In 1988, the National Geographic Society reopened Peary’s records and concluded that he hadn’t made the North Pole either.

Even if the expedition had made it; Peary wouldn’t have been first.

That accolade would have gone to Matthew Henson, the son of Maryland sharecroppers and Peary’s right-hand man.

In the final, demanding days of the expedition, it transpired that Henson had trudged ahead. Peary himself had "crippled feet" and was being dragged upon a sledge.

As they set up camp, Henson overheard the Inuit speaking about Peary’s plan to continue the final stretch alone and claim the Pole.

Henson, though, wasn’t worried.

Peary hadn’t taken any measurements for five days and his right-hand man believed they’d already reached their destination.

“One can tell to within a mile or so how far he walks in that northern ice,” Henson told the Boston Globe in 1910, “I reckoned that we were even now at the very Pole.”

After setting off with two Inuit companions, a sullen-faced Peary returned an hour later and ordered the American flag to be planted in the ice near where Henson stood.

Whatever way history looked upon it, Peary was beaten.

Pole In One

So it was down to a high school drop-out, Ralph Plaisted, to make the first confirmed surface conquest of the North Pole.

In 1967 the American completed the trip on a snowmobile with three companions (although by that point the Soviets had made several plane landings and the US Navy had completed the journey by sea).

Nevertheless, Plaisted had succeeded where those before him failed and earned himself a place in the record books.

A portrait of Robert Peary in Arctic furs from 1909

A portrait of Robert Peary in Arctic furs from 1909Creative Commons / Benjamin B. Hampton

Do you have any Feedback about this page?

© 2026 Columbus Travel Media Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission, click here for information on Columbus Content Solutions.

You know where

You know where