Discovering the spirit of Istanbul in Berlin

In the wake of Berlin’s annual Spirit of Istanbul Festival, Emilee Tombs ventures to Kreuzberg to find out how a “temporary” Turkish community has rooted itself into the German capital.

Exiting the Schönleinstrasse U-Bahn station in southeast Berlin on a Sunday afternoon I enter the neighbourhood of Kreuzberg, or as it’s more commonly known to Berliners, Little Istanbul.

Apart from the ubiquitous graffiti-covered buildings, the area seems entirely removed from the Berlin I’ve experienced over the past few days of my trip.

Gone are the artisan coffee shops, nameless fashion boutiques and bearded hipsters, and in their place stand kebab shops, halal butchers and chattering women wearing embroidered headscarves, their ears heavy with yellow-gold filigree earrings.

Turkish men crouch on their haunches along the Kottbusser Bridge, smoking and arguing with their colleagues, unnerved by the sub-zero temperatures of early spring. I meander merrily along Maybachufer, a market street that runs perpendicular to the tree-lined Landwehr Canal.

Kreuzberg's markets are a culinary delight

Kreuzberg's markets are a culinary delightCreative Commons / Jesse Garrison

Glancing through the stalls I eye swollen aubergines, golden falafel, rose-scented Turkish delight and reams of jewel coloured fabric. I stop at one of the stalls and pay a paltry €1 for 100g of the best caramel-sweet Medjool dates I’ve ever tasted. The raspy chattering of German and Turkish tongues hang continuously in the air.

Kreuzberg began its transformation from rundown German suburb to vibrant cultural melting pot in 1961, when the German and Turkish governments devised a plan that would both ease the pressure of Turkey’s unemployment crisis and help rebuild Berlin’s devastated infrastructure after WWII.

Many of the Turkish gastarbeiter, or "guest workers", invited to colonise Kreuzberg never left, staying on to claim the area for themselves and turning it into what is known today as Little Istanbul.

After more contented wandering – during which I sample several varieties of hummus – I make my way to Bateau Lvre, a kind of wreck bar with peeling paint and mismatched light fittings on the corner of lively Orienienstrasse. Inside I overhear a group of Berliners talking animatedly about a protest planned for the weekend.

Drawn to the exhilarating prospect of controversy, I chat up a local tour guide, an Englishman named Alex, who, in exchange for a well-priced Sternberg beer, tells me about the area he has come to adore over the past five years. Kreuzberg, he claims, is one of the most exciting places to live in Europe, never mind Berlin.

Orienienstrasse gets lively in the evening

Orienienstrasse gets lively in the eveningCreative Commons / Alexander Rentsch

"Peaceful protests and demonstrations are a regular occurrence in Kreuzberg because the locals here know they can affect a change," he says, before gulping his lager.

"When people get together in their thousands to support a widow who can no longer afford her rent and is being threatened with eviction by the local government, that government listen, and the widow is allowed to stay," he adds, "It’s an electric way to bring about change, and we love it."

Another of Kreuzberg’s most famed, and gleefully told, triumph-over-government stories is about a man named Osman Kalin, owner of what Alex calls the 'Baumhaus an der Mauer' ('The Treehouse on the Wall').

Like many of the local residents of Kreuzberg, Kalin refused to decamp back to Turkey after helping rebuild the city. When the GDR built the Berlin Wall, and Kreuzberg became a part of West Berlin, a triangle patch of land on a street in Bethaniendamm was accidentally left in limbo - it was owned by the east and marooned in the west, cut off by the wall.

The Baumhaus was initially built from scrap

The Baumhaus was initially built from scrap

Emilee Tombs

The land quickly became a dumping ground for locals, but Kalin took it upon himself to clear the rubbish, first moving, and then slowly salvaging, useful bits and pieces to create a communal garden from which to grow herbs and vegetables. After a while he realised the potential in some of his finds and started to build a house on the garden patch.

By the time the Wall came down in 1989, Kalin had erected several walls and built a two-storey home, with a working kitchen, lounge and bedrooms for his growing family. The government put pressure on Kalin to move out but thanks to peaceful protests and interventions by the local church he was able to stay. Despite now being over 90 years old, he still lives there.

Standing in front of the Baumhaus today you are greeted by the sight of a large ramshackle structure cobbled together with doors, fence posts, sheets of corrugated iron and various other curiosities. It’s a perfect example of the sense of community that emanates from the streets of this neighbourhood.

Of course, as it becomes more popular with creative types and other young professionals, gentrification will come creeping into the area and prices will rise. But for now, Kreuzberg clings defiantly on to its nickname, Little Istanbul.

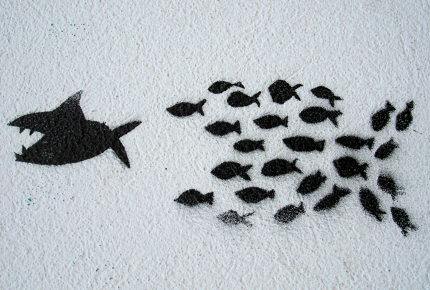

Together we are strong: the area's mantra summarised in its art

Together we are strong: the area's mantra summarised in its artCreative Commons / Gertud K.

It remains the best place in Berlin (and arguably, the world) to eat a doner kebab – it is, after all, the birthplace of this venerable dish – and is scattered with tiny, counter-service restaurants serving delicious shawarma (spit-grilled meat) wraps for a bargain €3.50.

The night I’m due to fly home I have a last meal in the Ottoman-styled institution Hasir, and to my delight I hear the story of Osman Kalin being told to a new group of travellers as they begin to tuck into their platters of moutabel (spicy aubergine dip) and pitta.

I sling back a shot of Raki (an anise-flavoured spirit from Turkey) in a toast to Kreuzberg and its citizens, who, in a city that is changing fast, cling on to protect their absorbing culture. Now that’s something worth celebrating.

NEED TO KNOW

How to get there: Flights from London Gatwick to Berlin Schönefeld start at £60 return.

Where to stay: The quirky Michelberger Hotel (tel: +49 30 2977 8590, www.michelbergerhotel.com) offers double rooms from €60. While the nhow (tel: +49 30 290 2990, www.nhow-hotels.com) is a swanky alternative with a modern décor. Double rooms start from €90.

More information:

Free walking tours: www.alternativeberlin.com

Tourist website: www.visitberlin.de/en

Travel information: www.bvg.de/en

Do you have any Feedback about this page?

© 2026 Columbus Travel Media Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission, click here for information on Columbus Content Solutions.

You know where

You know where